Raïssa Venables is a US-American photographer who has gained international recognition for her unique photographic installations. Her compositions are characterized by distorted, falling lines that seem to pull the viewer into the image. Using numerous photographs of interiors, objects, and everyday items, the artist digitally assembles them with great precision, creating multi-perspective works that often push the boundaries of reality. The perception itself is challenged, as the overloaded images create a sense of tension and claustrophobia, while the viewer simultaneously falls into a trance-like state of disorientation. Whether depicting tents, elevators, or interior spaces, Venables’ images capture the vibrant, pulsating life of these places.

Category: Uncategorized

Piet Wessing, Dealey Plaza, 1999

Jyrki Parantainen, Rosemary, 2006

Belonging to the series Dreams and Disappointments from the mid-2000s, all three works by Jyrki Parantainen in the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen’s current exhibition, a touch of playfulness, are images of images. For decades, the conceptual artist has been photographing landscapes and staged scenes that he then overlays with words and sentences and alters by adding pins and metal wires to their surfaces. By incorporating language and additional materials into his photographic work, Parantainen presents viewers with a chain of associations and invites them to consider what is not pictured.

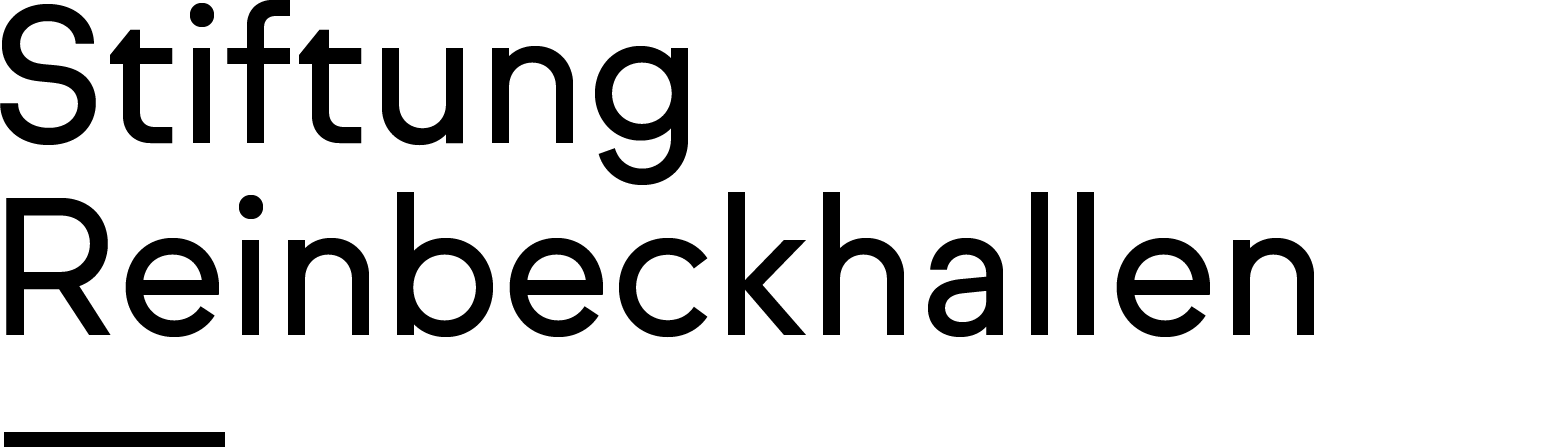

Sue Williamson, Truth Games, 1998

In the mid-1990s, a liminal period that saw the end of apartheid and the advent of democracy in South Africa, Sue Williamson (*1941 in Lichfield, United Kingdom) began to explore the role that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a committee tasked with investigating human rights abuses committed between 1960 and 1994, played in the healing of post-apartheid South Africa. Williamson’s probe, which involved the celebrated artist collecting images and excerpts from the transcripts of individual cases that circulated in newspapers at the time, resulted in the series Truth Games.

Completed in 1998, Truth Games includes twelve interactive works, two of which belong in the collection of the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen. All of these works share particular formal and conceptual qualities: their backgrounds are comprised of three grainy images depicting, from left to right, the accuser, the crime in question, and the defender, and are overlaid and dissected by ten horizontal slats. The latter provide the support for sliding panels that bear phrases from the transcripts and that invite viewers to not only engage directly with the multi-media works and their possible readings by shifting their positions, but to also question whether the testimonies of the TRC were effective in revealing the truth and helping the country to move forward.

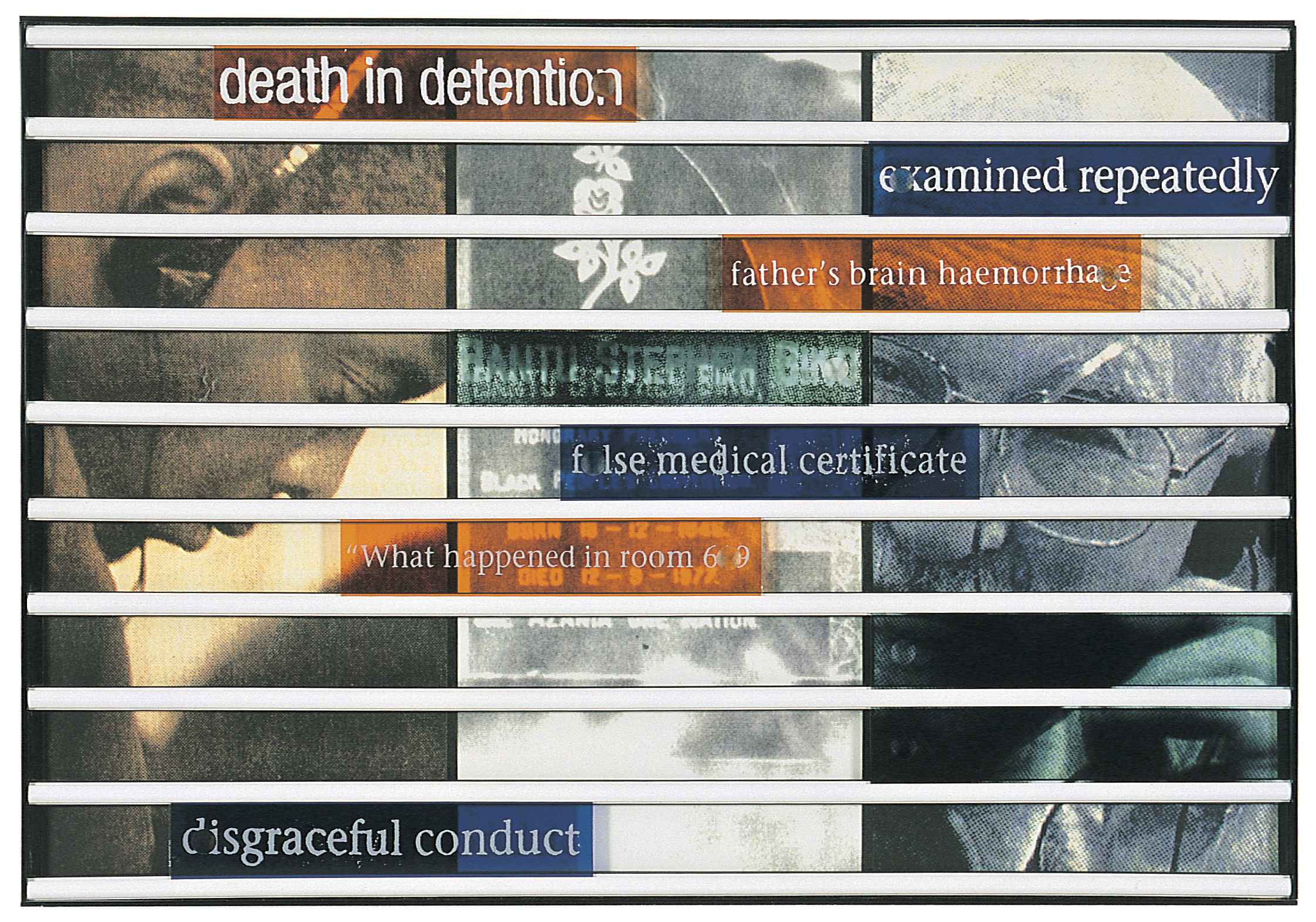

Paul Graham, a shimmer of possibility, 2018

The trips that Paul Graham took through the United States—the British-born photographer’s adopted home since 2002—for the photo compendium a shimmer of possibility (MACK 2018) seem to meander just like the different photographic genres he moves across. Landscapes, portraits, street scenes, close-ups and still lifes make up this body of work, consisting of twelve individual photography books. The size of the books, the theme of everyday life in America in the 2000s, and the concept of the photographic short story underlie all twelve series, which vary in their number of photographs, from one up to 60.

Considered to be one of the defining photography books of the 21st century, a shimmer of possibility was awarded the Paris Photo-Aperture Prize in 2012 for the most significant photography book published in the last 15 years and its first edition was sold out after ten weeks.

A collection of 15 posters by Cuban artists, 2009

Accessibility is undeniably one of printmaking’s most important features. From its production to its reception, this art form offers an enormous potential to provoke cultural and socio-political debate. Aligned with the interest of nurturing social discourses, with the activities of the Reinbeckhallen’s onsite printing workshop Werkstatt Neue Drucke and in dialogue with the exhibition program, a collection of 15 posters from a film and graphics portfolio, edited by the Taller Experimental de Grafica de la Habana, was purchased by the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen in 2018.

This acquisition was the result of the first closer cooperation of the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen with the Werkstatt Neue Drucke – coordinated since 2017 by Ulrike Koloska at the Reinbeckhallen – in the context of Otro amanecer en el trópico, an exhibition which presented a reflection on the contemporary artistic practices in and around Cuba.

In preparation for the exhibition, a research trip to Havana led by the curator Tereza de Arruda provided an overview of the artistic and cultural scene on the capital of the island, based on the one hand on the state institutions and on the other on the non-institutionalized art initiatives and the artists themselves.

Roger Melis, Christa Wolf, 1968

After completing an apprenticeship in photography in Potsdam in the late 1950s, East German photographer Roger Melis began working as a scientific photographer at the Charité, a hospital in East Berlin. Around the same time, Melis was asked to photograph German artists, writers, and singers for a book that was regrettably never realized. Despite this, his photographs were widely seen and celebrated at the time, so much so that by the end of the 1960s, when he was sought after by publications on both sides of the Berlin Wall, Melis decided to leave the hospital to work solely as a freelance photographer.

Several of these portraits, including one striking image of Christa Wolf from 1968, belong in the collection of the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen. In this black and white photograph, the admired East German writer is seen leaning against a chair in the comfort of her own apartment with her hands clasped together and eyes staring intently at the photographer and his camera. It is one of many portraits taken by Melis that places—both then and now—a spotlight on East Germany’s prominent cultural figures.

Nina Ansari, I Carry no Ca$h, 2011

Nina Ansari (b. 1981 in Tehran) has created an extensive oeuvre comprised of installations, paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and photography. With this complexity, she reserves an artistic and conceptual freedom. As different as these media are, they are united through the conceptual approach as well as Ansari´s biography, which runs like a thread through her work.

Her family fled to Germany during the first Gulf War when Ansari was four years old. A key moment for her in Iran was, when the interior of her house was briefly lit up by bomb blasts. The flash of light led to a new perception of reality. In her theoretical and photographic thesis Der Blick in die Fotografie (2010), Ansari dealt with the sense of sight, the human eye and the concept of seeing and gazing by examining the complexity of our perception with a camera. She described her role as an artist as an active one, the camera as a weapon, the approach as a conceptual one. The goal was to define the scope of photography. Today in retrospective she says, that she has exhausted this topic and thus answered the subject of photography for herself.

Dan Perjovschi, untitled, 2017

Featuring the work of Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi, Drawing Politics was the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen’s second exhibition. Today, almost five years later, the site-specific installation made by the artist in the Reinbeckhallen’s exhibition hall appears, especially given recent events, in a new light and yet loses none of its topicality.

Perjovschi worked in the exhibition hall in the run-up to the opening of Drawing Politics, designing his works—drawings and collages—directly on the walls. The works seem like a direct, immediate response to an experience, an article or an image, and are put down on paper only once a suitable base has been found. The drawings, however, are researched well in advance, optimized and refined time and time again. They comment on social phenomena, established structures, abuses, and world politics or on things that personally affect the artist.

Sibylle Bergemann, Frieda, Allerleirauh, 1988

In the mid-1960s, Sibylle Bergemann began her foray into photography by documenting windows, a subject that she would return to throughout her career, and by learning as much as she could about the medium from Arno Fischer, Elisabeth Meinke, Roger Melis, Brigitte Voigt, and Michael Weidt, all members of Gruppe DIREKT. By the end of the decade, Bergemann was regularly accepting assignments from East German illustrated magazines, including Sibylle: Die Zeitschrift für Mode und Kultur.